Mark Arthur

|

A full-blood Nez Perce, born in 1873. His mother being captured with Chief Joseph's band in 1877, Mark became a wanderer among strange tribes until about 1880, when he found his way back to the Nez Perce res., Idaho, where he entered the mission school of Miss McBeth and soon began to prepare for the ministry. When the Nez Perce captives sent to the Indian Territory were returned to their northern home, Mark found his mother among them and cared for her until her death . About 1900 he was ordained by the Walla Walla presbytery and became pastor, at Lapwai, Idaho, of the oldest Presbyterian church west of the Rocky Mountains, in which charge he has met with excellent success. In 1905 he was elected delegate to represent both whites and Indians at the general assembly of the Presbyterian church.

|

Smohalla

|

An Indian prophet and teacher, the originator of a religion current among the tribes of the upper Columbia River and adjacent region in Washington, Oregon and Idaho, whence the name "Smohallah Indians" sometimes applied. The name, properly Shmoqula, signifies "The Preacher," and was given to him after he became prominent as a religious reformer. He belonged to the Sokulk, a small tribe cognate to the Nez Percé and centering about Priest rapids on the Columbia in eastern Washington. He was born about 1815 or 1820, and in his boyhood frequented a neighboring Catholic mission, from which he evidently derived some of his ceremonial ideas. He distinguished himself as a warrior, and began to preach about the year 1850. Somewhat later, in consequence of a quarrel with a rival chief, he left home secretly and absented himself for a long time, wandering as far south as Mexico and returning overland through Nevada to the Columbia. On being questioned he declared that he had been to the spirit world and had been sent back to deliver a message to the Indian race. This message, like that of other aboriginal prophets, was, briefly, that the Indians must return to their primitive mode of life, refuse the teachings or the things of the white man, and in all their actions be guided by the will of the Indian God as revealed in dreams to Smohalla and his priests. The doctrine found many adherents, Chief Joseph and his Nez Percé being among the most devoted believers. Smohalla has recently died, but, in spite of occasional friction with agency officials, the "Dreamers," as they are popularly called, maintain their religious organization, with periodical gatherings and an elaborate ceremony. See Mooney, Ghost Dance Religion, 14th Rep. B. A. E., 1896.

|

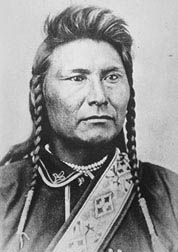

Lawyer

|

Throughout the entire history of settlement, Lawyer was a friend of the Whites. He was especially prominent in the negotiations with Governor Stevens after the great war of 1855. He threw the weight of his great influence in favor of the treaty, which established the existing reservations and confirmed the Indians in the property which they now hold. Though opposed in his peace policy by Owhi, Kamiakin, Peu-peu-mox-mox and Joseph, the persistence of Lawyer and the numerical strength of his people turned the scale in favor of the treaty. The benefit to the settlers by this event can scarcely be overstated. As was just, the astute chief was ever afterwards held in great favor.

In person Lawyer was a typical Indian. Though not of large stature, he was exceedingly straight and well-built with the eye of an eagle and the nose of a hawk. He has had few equals in general intelligence among his people.

"Lawyer" was a nickname given to Hallalhotsoot by the mountain men of the early 1830s. He was known as "the talker," and his speaking abilities and wisdom enabled him to influence both native and non-native peoples.

Lawyer devoted his life to making peace with the white population and following the terms of the treaties he signed. Nevertheless, in 1870—after holding his post for twenty-five years—he voluntarily stepped down from the leadership of the Nez Perce.

His descendants tell the tale of his death on January 3, 1876, in this manner: It was Lawyer's custom to fly his American flag from a pole in front of his lodge or house. On the day that he died, knowing that his end was near, he instructed some member to gradually pull down the flag. The flag would be lowered a bit and then Lawyer, after a time would say: "Pull it down a little more." So the flag was lowered a little more. This was repeated several times and when the flag touched the ground, Lawyer died.

|